Today we’re talking to Ben Wu and Jordan Toth who were the primary designers on CIPHER ZERO.

Could you please tell us a little bit about yourselves?

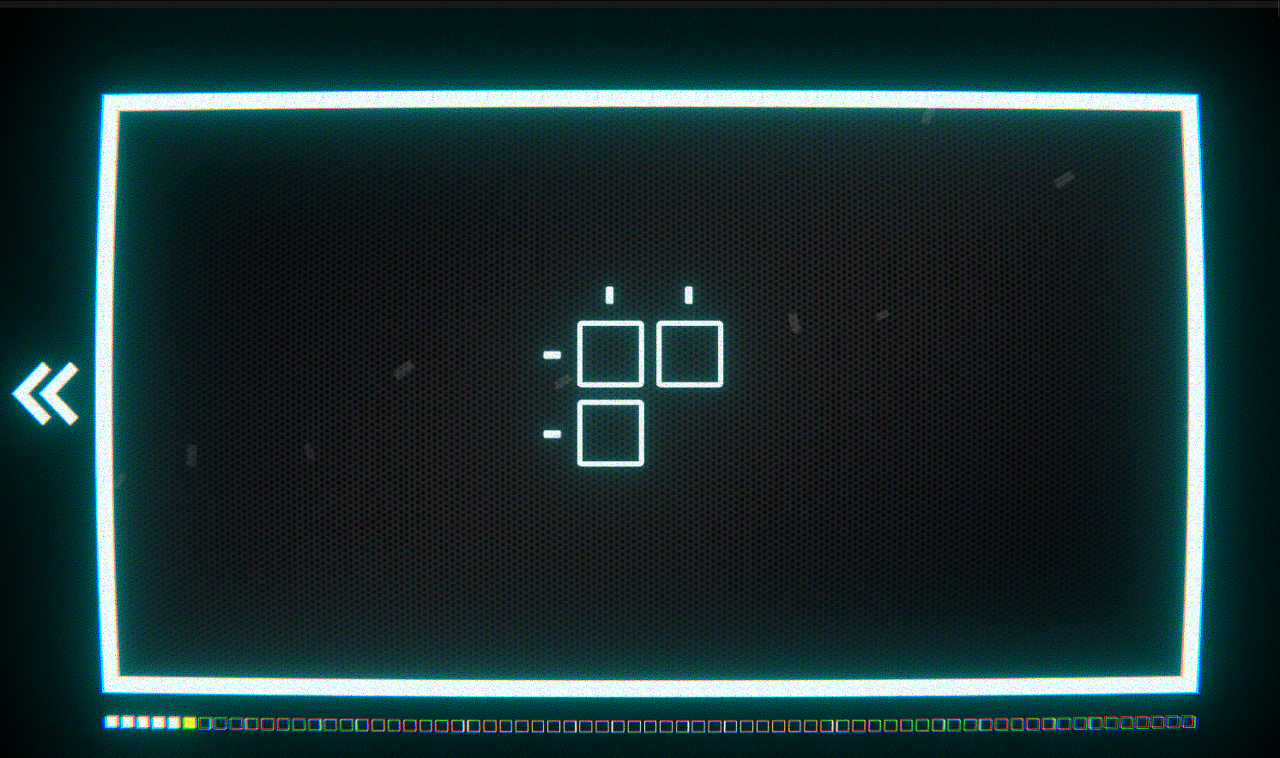

Ben: Hello! My name is Ben and I’m a Boston-based game developer and have been making games for about 8 years now. I’ve gotten to work as a gameplay-focused programmer on a bunch of larger projects including Spellbreak, Valorant, World of Warcraft, and Concord. I also spend a lot of my time tinkering with smaller projects as a designer, which is how CIPHER ZERO came to be!

Jordan: Hey I’m Jordan! I’m a software developer based in Brooklyn. I briefly worked in game development a while back, and now I’m mostly a game dev hobbyist.

So, getting into the thick of things, CIPHER ZERO was conceived at a game jam, Ludum Dare 45 specifically. Many game jammers who saw some success during their jam want to take their prototype to the next step but most won’t be able to act on it because of various challenging reasons.

What can you tell us about the first few steps of going from prototype to starting production?

Ben: We were very fortunate that the Ludum Dare version of the game ticked a bunch of boxes such that it felt natural to immediately start working on an expanded version. We knew the core premise of the game was really solid (folks playing the original version would often spend the better part of an hour playing it, which is a stellar outcome for game jam project) and we had a lot of ideas for new mechanics that we knew were neither going to be technically challenging nor require a lot of art support to implement.

Jordan: Once we decided to move forward with the game after Ludum Dare we knew that we would need a lot more content for the game.

Ben: Often it’s that final piece that feels the most daunting when taking a new project forward: the amount of time and effort it would take to make more content. Because CIPHER ZERO is a minimalist puzzle game, the biggest barriers moving forward after the game jam were all game design challenges, which were surmountable by a team of two people.

Jordan: We went back to the drawing board and looked at some puzzle mechanics that we had considered for the jam and decided against, and continued brainstorming for some brand new ones as well. We also did a ton of playtesting even just with the prototype version to see if players were getting stuck on any particular puzzles, so we could refine what we already had.

It’s one thing to make a plan and another thing to actually carry it out. It’s easy for a lot of people to get stuck in the planning stage and never move on.

What do you think were the key factors that made you feel comfortable about moving forward building a full game?

Ben: It was primarily the great feedback we would get from folks playing the game jam version. We knew we had already figured out the core premise of the game so it felt like from that point that all we needed to do was create more.

Jordan: Yeah, it was definitely the volume of positive feedback we got from the jam game. We had friends sharing it with other friends, people coming back to us and outright telling us they wanted to keep playing more. Some folks asked me who the developers were, thinking I was just sharing a game I had enjoyed, and I had the joy of telling them “me!”

Why the name “CIPHER ZERO?”

Jordan: I think Ben came up with the final name! The game was originally entered to Ludum Dare under just the name “Cipher” after some cryptography-centered brainstorming.

Ben: “Cipher” felt like a natural name for the original game jam project since the gameplay is about decoding a solution from minimalistic symbols and prior knowledge.

Jordan: But you would not believe how many games there are with a name like “Cipher” already. We were attached to the name Cipher so we started brainstorming ways to make it more unique.

Ben: We added “Zero” to the title of the full game as a nod to the original Ludum Dare 45 prompt “Start With Nothing”.

There’s an enormous amount of puzzles in CIPHER ZERO. And they’re all handmade, nothing done through procedural generation?

Ben: I think at this point the full game will actually have closer to 400 than 300, and they are all made by hand. We did experiment with creating puzzles with procedural generation but ultimately we needed to communicate a set of ideas to the player very precisely so going with handmade really was the only option.

How did you go about creating that many puzzles by hand?

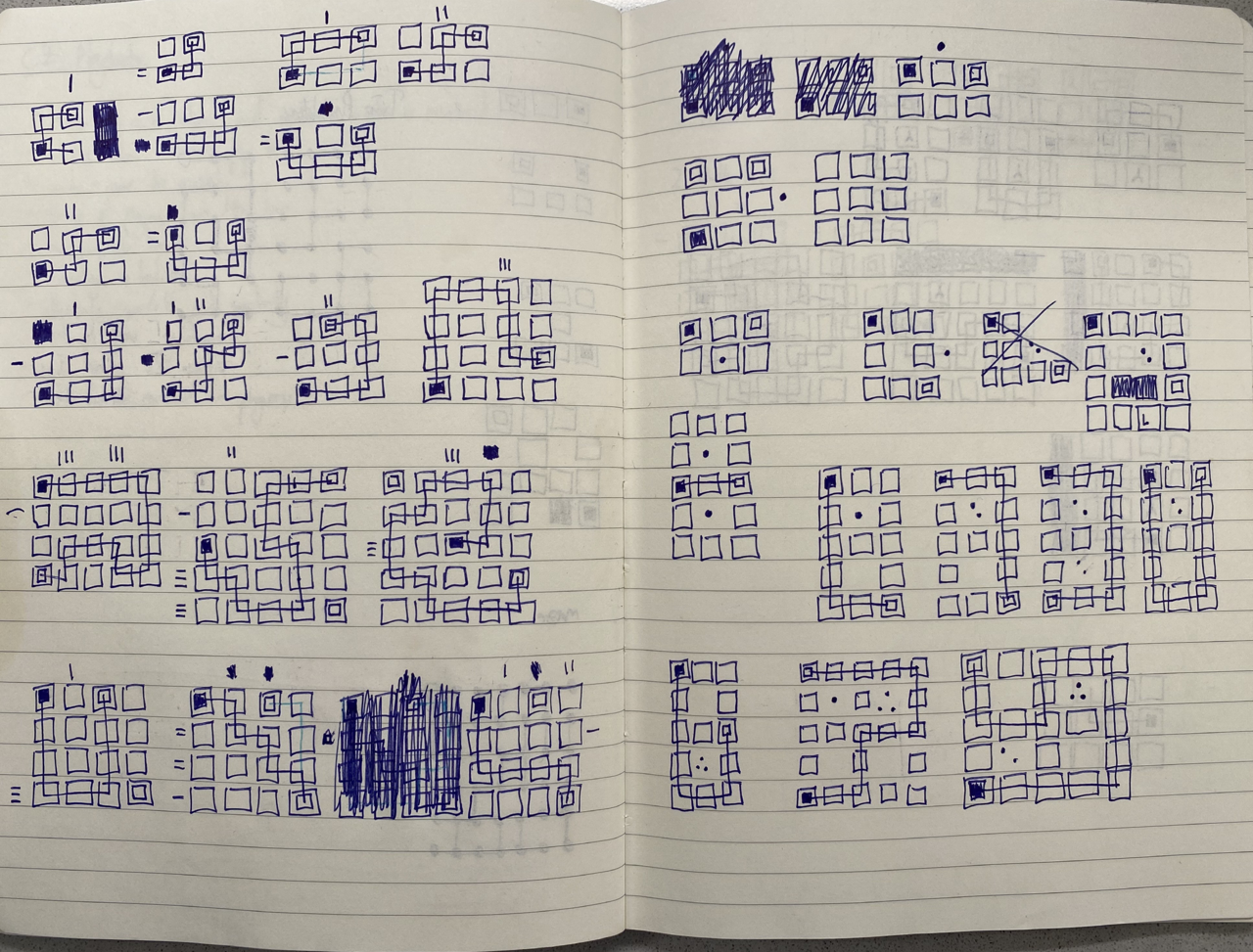

Ben: The primary question we are asking ourselves when designing a puzzle is “what are trying to teach the player with this puzzle?”

To most effectively teach a player a new idea via puzzles, we found that puzzles are best grouped into four sets:

- The first set of puzzles would communicate foundational elements

- The second set would test that foundational knowledge

- The third set would start combining the new idea with existing ideas that the player has already encountered

- The fourth set would then start testing that holistic knowledge and challenging assumptions that the player may have made up to that point.

This kind of structure is best when teaching anyone anything, really, but it was core to CIPHER ZERO since the game is constantly introducing new ideas.

Jordan: I find those last ones are the hardest to keep interesting, and I know Ben and I had very different processes when working on these. Ben often starts with an interesting visual design for the layout and the solution then refines it until it’s satisfying to play through, and I often start with tricks I want to pull on the player, an approach I think someone might try at first glance that ultimately won’t work.

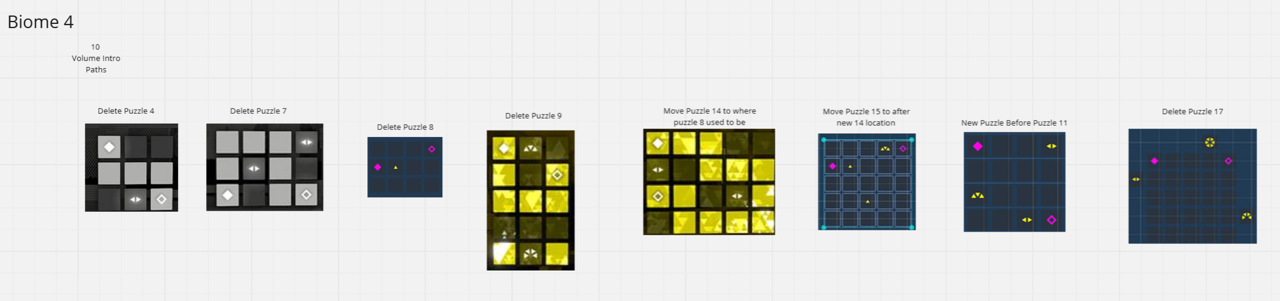

Ben: Keeping things interesting was about making sure that every puzzle was either teaching the player something new or challenging them on their existing knowledge in a new way. Practically speaking this meant that there was really aggressive cutting of puzzles down to what we thought was the bare minimum number of puzzles needed to communicate the full set of ideas and mechanics to the majority of players.

What were some of the challenges you faced when designing these puzzles?

Ben: One challenge was maneuvering around the decision to make the game fully linear, a direction I’ll probably not make again if I make another puzzle game in the future! Because each puzzle needs to be completed by the player in a specific order, we needed to spend a lot of time balancing the difficulty such that players who are new to the “thinky puzzle game” genre wouldn’t feel overwhelmed while still giving veterans of the genre an engaging challenge.

Jordan: An unexpected challenge was actually cutting puzzles! In order to maintain good pacing we had to make sure that the puzzles slowly scaled in difficulty as the player learned more and more, and that meant that some puzzles I liked had to be cut because they were too similar to other puzzles that were even better.

Sometimes we were able to rework the core idea of a puzzle into something harder to keep a good difficulty curve, but some puzzles did end up on the cutting room floor, and deciding which ones would end up there was hard. No one likes to see their work end up unused but sometimes less is more!

How fast could you crank out puzzles when you were on a roll?

Ben: It was always a pretty slow process. Once a particular mechanic was established, it was pretty easy to make a lot of puzzles, but the trick was creating a sequence of puzzles that taught the player all of the ideas we wanted them to understand, in the order we wanted them to understand them, and without lingering on any of them for too long.

Jordan: I think the fastest I ever got at making new puzzles was probably during the game jam. We were starting from nothing—

Hah!

Jordan: —so we had a lot of very basic puzzles to introduce players to the game right at the start. Even then though I think I was at best making maybe 15 or so usable puzzles over the course of maybe two hours. I can be a bit of a perfectionist and I’ll tinker with a puzzle forever if left to my own devices.

Do you have a favorite puzzle or type of puzzle from the game? Can you tell us a bit about it? (No spoilers!)

Ben: My favorites are the puzzles that require the player to think less mathematically and more spatially, where finding a solution feels less about eliminating possibilities with constraints and feels more like creative discovery.

Jordan: Sometimes when we introduce a new mechanic, we find that playtesters have a misconception about what the glyph means. We try to teach using the early puzzles, but sometimes there’s another conclusion that isn’t contradicted in any of the early puzzles. So after playtesting we’ll go back and design new puzzles that specifically disprove these conclusions.

I loved making these kinds of puzzles. It required really getting into players’ heads and figuring out what they were thinking about a mechanic, and then figuring out how we could design a puzzle that really clearly disproves the notion in their heads. There’s even one idea that was so persistent for a lot of players that we had to sprinkle puzzles throughout the puzzle set to remind players that a particular mechanic didn’t work a particular way.

For the full version of the game, you collaborated with Zapdot. I’m sure there are people out there who are looking for similar partnerships with a studio to get an internal project off the ground. What can you tell everyone about your experience and the key takeaways from this partnership?

Jordan: I’m going to leave this one to Ben, he was the main point person for the collaboration.

Ben: Jordan and I started working with Zapdot on the project after the studio’s owner, Michael Carriere, expressed interest in collaborating to finish the project after he saw an expanded version of the original project. It’s a pretty unique scenario that was a result of a lot of circumstances perfectly lining up so I can’t really give advice to folks who want to look for similar partnerships.

What I can say though is that, more generally, if you’re an independent developer deciding whether or not to expand the team, you have to evaluate whether or not the extra folks you’re considering bringing on would bring on new skillsets or experience and whether or not those unique skillsets or experience is needed for your specific project.

In this regard it was a no-brainer of a partnership for us. Jordan and I already had a project with really solid gameplay foundations and Zapdot had a wealth of experience in basically everything else required to take a game like this over the line.

Sometimes there’s a misconception that the designer is just the ‘idea guy’ with a side of spreadsheets. When it comes to QA and playtester feedback, you’re actually pretty involved, right?

Ben: Yup, we are extremely involved! Anytime anything changes, even stuff one wouldn’t consider to be “core gameplay”, we’re closely watching playtesters to see how they respond and we make adjustments accordingly.

What are some things you watch out for when it comes to playtests and how do you go about adjusting things from the feedback?

Ben: I personally think, as a designer, you get the most valuable feedback from simply watching the player play your game with zero intervention and paying really close attention to the differences between how you are hoping/expecting the player to respond and how they actually respond. Did the player understand this idea after we attempted to teach it to them? Did they come to incorrect conclusions about something and, if so, why is that? What is their body language like? Are we holding their attention in this moment?

Jordan: I particularly look for when players are struggling with early puzzles, and for when players are trying a strategy that I think has already been disproved in an earlier puzzle. That’s often a sign that the rules of a mechanic are ambiguous to players, and we need to add more puzzles to reinforce some of the ideas we’re trying to teach players. I definitely love trying to get into the players’ heads and figure out what they’re thinking, when helps us refine the game experience.

With CIPHER ZERO available to everyone in just a few days, what are you most excited for?

Ben: I’m just excited for folks to be able to play it!

Jordan: Ever since the game jam the single thing that’s consistently gotten me excited is the thought of people playing my game. It was incredible to see people enjoying my work during the jam, and showing it at conventions and expos was downright surreal (and our biggest problem was that no one wanted to put it down!). So I’m just excited for even more people to play it.

Lastly, do you have anything you want to say to all the CIPHER ZERO players (and players-to-be) out there?

Ben: It’s a game about trial-and-error, so missteps are part of the process! And please enjoy!

Jordan: Be ready to challenge your ideas, don’t assume you’ve got something figured out just because your idea worked on a few puzzles. The more open-minded you are about what’s right and wrong, the easier time you’ll have with CIPHER ZERO. And I hope you enjoy it!

Thank you both for your time! It was great working on this with you and this is everyone’s reminder that CIPHER ZERO is out on July 22nd.

Please wishlist and tell us on Bluesky or Discord if you decide to stream it — we’d love to watch.